Highlights from the Collection: Egypt

The Oriental Institute Museum houses nearly 30,000 artifacts from the Nile Valley that were acquired through archaeological excavations or purchase. The first significant group of objects was purchased by Oriental Institute founder James Henry Breasted on his honeymoon in Egypt in 1894. In the following years, thousands of objects were received from the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Society) and the British School of Archaeology in Egypt who conducted excavations throughout Egypt. These donations were made in exchange for the University of Chicago’s financial sponsorship of their work. Another important group of approximately 8,000 objects, including our colossal statue of King Tutankhamun, came from the Oriental Institute's excavations at Medinet Habu from 1926 to 1933. Today, the Oriental Institute Museum’s Egyptian collection is one of the largest and most complete in the United States.

Fragment from the tomb of Diesehebsed

This block came from the now lost tomb or tomb chapel of a woman named Diesehebsed, who is shown to the left. She bore the title Singer in the Interior of the Temple of Amun, indicating that she was part of a divine chorus that entertained the god during offering rituals. Traces of hieroglyphs in the cartouche before the woman to the right identify her as the God's Wife Amunirdis II. Another scene of the two women together is known from the Karnak Temple, suggesting that Diesehebsed was a trusted administrator of the God's Wife, who during this period was the virtual ruler of Thebes. Diesehebsed was from one of the most prominent families of Thebes. She was the daughter of Nesptah, who was a Priest of Amun and the Scribe of the Offering Table, indicating that both father and daughter worked for the administration of Amun at Thebes. Diesehebsed was also the sister of Mentuemhat the mayor of Thebes. Blocks from his huge tomb at Thebes are shown elsewhere on this Web page.

Magical Bricks

On display in the Oriental Institute Museum are two "magical bricks" from an ancient Egyptian tomb. They are made from finely sifted Nile clay and left unbaked, rather unlike your typical architectural sun-baked mud brick. Magical bricks were inscribed with selections from Spell 151 of the Book of the Dead. According to the rubric, which provides the manufacturing and placement instructions, four bricks and four amulets set in the bricks were produced for each tomb. Placed into niches in the wall or on the floor of the burial chamber, magical bricks protected the deceased at the cardinal directions by warding off potentially dangerous entities. The designation "magical brick" derives from their rectangular shape, their designation as "brick" in ancient Egyptian texts, and their apotropaic function within the tomb. There is nothing particularly "magical" in a Western sense about magical bricks, for the properties which we would consider "magical" were notions that existed within the logical cosmology of ancient Egyptian religious traditions.

OIM E6776 and OIM E6777 are two rather small magical bricks measuring 6.5 by 4.0 by 1.5 cm - quite easy to miss with all the other beautiful objects displayed in the Joseph and Mary Grimshaw Egyptian Gallery. Members of the Egypt Exploration Society excavated them in tomb D13 at Abydos and gave them to the Oriental Institute as part of the distribution of finds to excavation supporters. Buried in Abydos tomb D13 was the Twenty-fifth Dynasty vizier Nespaqashuty C, father of the vizier Nespamedu (Abydos tomb D57) and grandfather of the vizier Nespaqashuty D. Portions of Nespaqashuty D’s tomb (Theban Tomb 312) are also on display in the Egyptian Gallery. If Nespaqashuty C had a complete assemblage of magical bricks, the other two bricks have been lost or destroyed in antiquity. Damage to both bricks occurred at some point since the amuletic figure of OIM 6776 and the amuletic wick of OIM 6777, which left indentations and a hole respectfully, have never been discovered.

Text of OIM E6776

O’ you who comes to entangle, I will not allow you to entangle me. O’ you who comes to assault me, I will not allow you to assault me. May I entangle you. I will dispel you. I am the protection of the Osiris, vizier, Nespaqashuty. On the north, facing to the south.

Text of OIM E6777

I am the one who drags things to block the hidden ones and who repels the activities of the one who displaces those who are in the torch of the necropolis. I have lit up the desert. I have confused their path. I am the protection of the Osiris, vizier, Nespaqashuty. On the south, facing to the north.

Text by Foy Scalf. Adapted from News and Notes vol. 203 (fall, 2009).

The Mummy and Coffin of Meresamun

Meresamun was a "Singer in the Interior of the Temple of Amun" at Karnak where she was part of a divine choir that sang and made music during temple rituals. Her coffin is made of cartonnage, a type of papiér-maché material composed of layers of fabric, glue, and plaster. Cartonnage coffins were formed over a temporary inner core made of mud and straw. After the coffin shell was completed, the core was removed and the wrapped mummy was inserted into the case through the back. The coffin was then covered with another layer of thin white plaster and painted. Representations of floral garlands cover the chest of the coffin. Below the garlands are the Four Sons of Horus who guarded the viscera, and a falcon with sun disk, a reference to the rebirth of the deceased each day with the rising sun. The vertical text is a prayer calling upon the gods to give funerary offerings to Meresamun. The pigments are original. This type of mummy case was normally part of a more complex set of coffins and would have probably been placed within one or more wooden anthropoid (human-shaped) coffins. Nothing is known about the location of Meresamun’s tomb or why she died at the relatively young age of 29 or 30.

Coffin for a Lizard

Animal mummification gained popularity in first millennium BC. During this time, mummification included even small creatures, such as snakes, shrews, and scarab beetles. Some animals were buried in coffins made of metal, wood, or clay. The mummified remains of small animals in particular were often placed in bronze coffins. Their likeness was rendered in bronze on the lid of the coffin. This example once contained a mummified lizard. The coffin has corroded shut, but remnants of the lizard still rattle around inside. The lizard was associated with the creator god Atum.

Ear Stela

Ancient Egyptians could worship their gods without going to a temple. This small stela is incised with five pairs of ears that represent a direct conduit to the god, much like an ancient mobile phone with a dedicated line to the deity. Although this example does not bear an inscription, other such stelae identify the ears as belonging to the god Ptah. These objects demonstrate how accessible the gods were thought to be; they could be contacted any time, any place, and asked to intercede on any sort of problem.

Funerary Stela

Recovered from a private tomb in the Ramesseum at Thebes, this painted funerary stela commemorates the lady Djed-Khonsu-iw-es-ankh. She is shown in a diaphanous white gown, wearing a perfumed cone and a water lily on her head. She pours a libation over a table of food offerings and raises her hand to greet the seated god Re-Horakhty, a form of the sun god. The hieroglyphic text is a prayer asking the gods to supply food and drink for the survival of her spirit in the afterlife:

An offering which the king gives to Re-Horakhty, the Great God, Lord of Heaven, that he may give invocation offerings consisting of offerings and food to the Osiris, Lady of the House, the noblewoman, Djed-Khonsu-iw-es-ankh, deceased, daughter of the priest of Amun-Ra, King of the Gods, Master of the Secrets of the Garments of the Gods, Ser-Djehuty.

Relief from the Tomb of Mentuemhat

The ancient Egyptians decorated the walls of their tombs with scenes showing the types of activities that they wished to continue to enjoy after death. This relief fragment comes from the enormous tomb of Mentuemhat, a governor of Thebes. One of the most powerful men of his time, Mentuemhat was able to employ the best artists to carve and paint scenes of abundance that would satisfy his every need in the afterlife. In the relief, papyrus reed boats travel through water teeming with fish. The boat on the left has an oarsman on the bow and stern. A third figure, probably an overseer as indicated by his staff of office, points his finger in a gesture of magical protection that was meant to avert danger, such as the attack of a hippo or crocodile. The men wear reed life vests across their chests.

Sistrum (Ritual Rattle)

A sistrum is a rattle that was played in religious processions and ceremonies. The crossbars of this example once supported metal disks or tangs that would have made a metallic clanging sound when the instrument was shaken. Like most sistra, this one is decorated with the head of the cow-eared goddess Hathor who was associated with music and dance. Above the goddess’s head is a tiny temple whose doorway is ornamented with recumbent lions. Inside the temple is the cat-headed goddess Bastet who holds her own tiny sistrum. A cat nursing her kittens appears on top of the sistrum. The complex decoration on this sistrum alludes to a myth of the Eye of the Sun in which Hathor, the daughter of Re, assumed the form of an angry lioness (or Nubian cat) who threatened to kill mankind because they rebelled against Re. Her anger was quelled by music and, once appeased, she assumed the form of Bastet. The cat on top of the sistrum alludes to the most pacified and peaceful form of a feline. The handle is in the form of the god Bes crowned with his feathered headdress. He stands on an open lily bloom flanked by two sphinxes. Bes and the lily are allusions to rebirth, for Bes was the god who guarded women and children, whereas the open lily symbolizes rebirth because the flower opens anew in the warm rays of the morning sun.

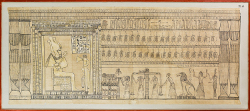

Book of the Dead (Papyrus Milbank)

The Book of the Dead was a collection of spells, hymns, and prayers intended to secure the deceased safe passage to the afterlife. This is one section of a papyrus that was originally 35 feet long. It shows the judgment of the soul before Osiris, the god of the dead, who determined the deceased's worthiness to enter the next life by assessing his earthly deeds. The heart of a man named Yartiuerow is being weighed in the balance against the feather of the goddess Maat, representing truth and justice. The jackal-god Anubis and falcon-headed god Horus stand below the scale. Thoth, the secretary of the gods, records the favorable verdict. Yartiuerow appears twice. Once, bowing before the scale, and to the right, his hands raised in jubilation, accompanied by a goddess with a feather head who may be Maat or the personification of the West. Between the representations of Yartiuerow is a monster-part hippopotamus, part crocodile, and part lion-called the "the Devourer" who would have consumed Yartiuerow’s heart should the judgment be unfavorable.

Trial Piece

It is uncertain whether this small relief is a student's practice piece or the unfinished work of a trained sculptor. Although the figure wears no royal insignia, it is probably pharaoh Akhenaten, depicted in the exaggerated style of the early period of Amarna art. The king’s unusual facial features which served as a model for all human representations during his reign, include narrow slanting eyes, a long nose, hollow cheeks, thick lips, and hanging chin. The sculptor has added incised lines to indicate the angle of the jaw and the crease that extends downward from the edge of the nose. Akhenaten wears a short Nubian or military-style wig; the detailing of the curls has been left uncarved.

Potter

This statue of a potter came from a group of twenty-five statues from the tomb of Ny-kau-Inpu, a cemetery official who was probably buried at Giza. The statues included representations of Ny-kau-Inpu and his wife, his family, and household staff. The statues were put in the tomb to serve as duplicates of the individuals, ensuring that Ny-kau-Inpu and his household would live forever. This figure is one of the earliest-known statues of a potter. It shows him squatting before a low hand-turned wheel as he forms a broad bowl. The arduousness of his profession is indicated by the way his ribs stand out on his back, how his skin is tightly drawn over his face, and by his deeply receded hairline.

Colossal Statue of Tutankhamun

This statue represents a king of late Dynasty 18, most probably Tutankhamun. It was usurped by succeeding kings and now bears the name of Horemheb. The king wears the double crown and the royal nemes head cloth. A cobra goddess (uraeus) that was thought to spit fire at the king’s enemies rears above his forehead. The king grasps scroll-like objects thought to be containers for the documents by which the gods affirmed the monarch’s right to divine rule. The dagger at his waist has a falcon’s head, symbol of the god Horus, who was believed to be manifested by the living pharaoh. The small feet at the king's left side were part of a statue of his wife, Ankhesenpaamun, whose figure was more nearly life-sized. The facial features of this colossal statue strongly resemble other representations of Tutankhamun, suggesting it was commissioned for him. Traces of the name of his successor, Aye, can be seen under the name of Horemheb in the cartouches on the back pillar, indicating that the statue was usurped twice. The Oriental Institute excavated two of these statues. One was graciously given to the University by the Egyptian government; the other is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Mummy Mask

The wrapped head and shoulders of mummies were often covered with a mask that served as a copy of the face of the deceased. It was believed that the soul of the deceased (ba), in the form of a human-headed bird, left the body during the day and returned to it at night. The mask was a duplicate head and face that ensured that the ba would recognize the mummy in case the body decayed. The ba is shown perched on top of the head. This mask is made of cartonnage, a sort of papiér-maché made from linen and papyrus. The cartonnage was coated with gesso before the paint and gilding were applied. The deceased is shown wearing a necklace at the throat with a heart amulet as a pendant. Below is a broad collar necklace fringed with drop pendants. A representation of funerary shrines with double doors appears on each shoulder. The god Osiris, with whom the deceased was associated, sits on top of each shrine.

Butcher Slaughtering a Calf

This statuette of a butcher is one of a group of sculptures placed in the tomb of the Egyptian official Ny-kau-Inpu. The Egyptians believed that the deceased lived on the afterlife and that he or she continued to need food and beverages. Rather than sacrificing actual servants, statues of workers placed in the tomb were thought to be able to perform duties eternally. Here a butcher prepares a trussed ox. His whetstone, attached to a strap, is tucked into his waistband.