Khorsabad Relief Project

Among the uncatalogued and unpublished objects in the basement of the Oriental Institute are as many as 1000 fragments of carved stone relief fragments from the palace of the Assyrian king Sargon II at Khorsabad. From 2006 until her death in 2012, Eleanor Guralnick, Research Associate at the Oriental Institute, worked with museum staff to identify, clean, photograph, and catalogue these reliefs.

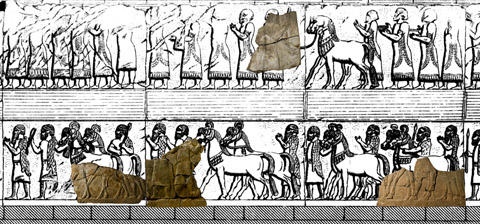

The Assyrian Empire of the ninth through seventh centuries BC was the largest the world had known, expanding by conquest and intimidation from its center in what is now northern Iraq as far as Egypt and Cyprus in the west and the Iranian plateau in the east. There were three cities that served as imperial capital during the empire: Kalhu (modern Nimrud), Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad), and Nineveh. The traditional capital city, Ashur, remained a ritual center of the empire. At the center of each capital city was a royal palace lined with carved stone reliefs that displayed the power of the empire to visiting emissaries, to imperial subjects, and to the court itself in scenes of ritual performance, battle with and defeat of enemies, tribute, and royal leisure.

The palace at Khorsabad was built by Sargon II between 717 and 706 BC and abandoned after his death in 705 BC. Khorsabad is unusual among the Assyrian palaces because of its stylistic innovations, the preservation of paint on its reliefs, and the extensive ancient written documentation concerning the organization of the building project. Khorsabad was excavated first by French archaeological teams in the nineteenth century and later by the Oriental Institute from 1928 to 1935. The sculptured stone slabs that once lined the palace walls were removed from the site and are now held by four museums: the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad, the Oriental Institute Museum in Chicago, the Louvre in Paris, and the British Museum in London. The collection of the Oriental Institute includes full relief slabs on display as well as approximately 100 cases of larger fragments and more than 350 smaller fragments in storage that remain unpublished and incompletely cataloged. Generally, discussion of the reliefs from Khorsabad has been based on drawings published in 1849 by Eugène Flandin, yet a cursory comparison of the drawings with the published sculptures makes it clear that many of the drawings omit details, including preserved traces of color, that would add significantly to our knowledge of Assyrian imperial art.

The study of the Oriental Institute reliefs will address a number of questions. Does close study of details of hairstyle, dress, ornament, and horse trappings on tribute bearers allow us to specify which peoples are represented? Does careful study of the inscriptions on the front and back of the reliefs confirm that they belong to a standard inscription, or are there significant variants that can inform us about the sequence of construction in the palace? Even minor variants might inform us about the existence of work groups in different areas of the palace. Masons’ marks that have only occasionally been noted may also provide insight into the construction process. Finally, analysis of preserved traces of pigment will give a fuller picture of the use of color on the reliefs and their chemical composition.

Further Reading: Guralnick, Eleanor. 2013. "The Palace at Khorsabad: A Storeroom Excavation Project." In D. Kertai and P. A. Miglus (eds.) New Research on Late Assyrian Palaces. Conference at Heidelberg January 22nd, 2011, 5–10. Heidelberger Studien zum Alten Orient 15. Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag.