- The Holy City of Nippur

- Early History of Excavations

- 11th to 19th Seasons

- Resumption of Work at Nippur

- Articles

- Annual Reports

The Holy City of Nippur

In the desert a hundred miles south of Baghdad, Iraq, lies a great archaeological mound sixty feet high and almost a mile across. This is Nippur, the city of Enlil, the "mooring-rope" of heaven and earth that for thousands of years was the primary religious center of Mesopotamia, where Enlil, the supreme god of the Sumerian pantheon, created mankind.

Although never a political capital city, Nippur had great religious importance as it could bestow legitimacy upon royal rule in Mesopotamia. Nippur was thus the focus of pilgrimage and building programs by dozens of kings including Ur-Nammu of Ur, Hammurabi of Babylon, and Ashurbanipal of Assyria. Despite the history of wars between various parts of Mesopotamia, the religious nature of Nippur protected it from suffering most of the destructions that befell cities like Ur, Nineveh, and Babylon. Nippur thus preserves an unparalleled archaeological record spanning more than 6000 years.

Settled around 5000 BC, Nippur played an important role in the development of the world's earliest civilization. The city, with its many temples, government buildings, and important family businesses, was probably more literate than other towns, and the scribes have left thousands of Sumerian and Akkadian documents written on clay tablets. Included among this extraordinary body of texts are the oldest versions of literary works, such as the Gilgamesh Epic and the Creation Story, as well as administrative, legal, medical and business records, and school texts.

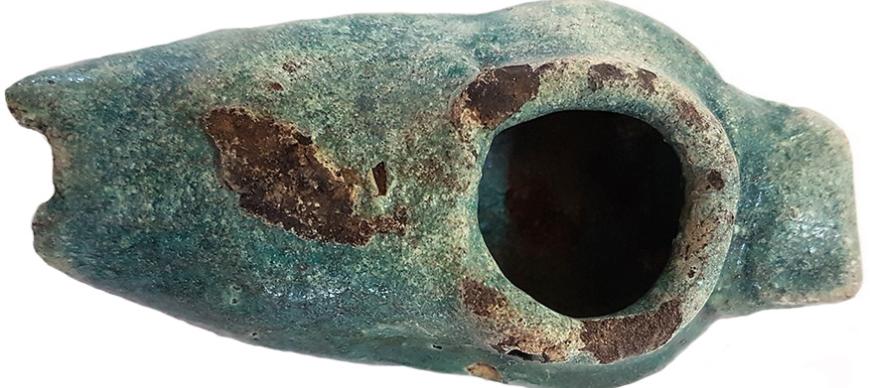

Objects can often tell us about things that were not written down. Elaborately designed items made of precious metals, stones, clayand shell allow us to reconstruct the development of ancient Mesopotamian art, as well as the far-flung trading connections that brought the materials to Babylonia. Egyptian, Persian, Indus Valley, and Greek artifacts also found their way to Nippur. Even after Babylonian civilization was absorbed into larger empires, such as Persian Achaemenid and that of Alexander the Great, Nippur flourished. In its final phase, prior to its abandonment around AD 800, Nippur was a typical Muslim city, with minority communities of Jews and Christians. At the time of its abandonment, the city was the seat of a Christian bishop, so it was still a religious center, long after Enlil had been forgotten.

Early History of Excavations

Americans have been doing research on Nippur for a hundred years. In 1888 the University of Pennsylvania sponsored the first American expedition ever to work in Mesopotamia. On the staff in that first season was Dr. Robert F. Harper, who a few years later founded Assyriological studies at the University of Chicago. The expedition worked at Nippur until 1900, finding more than 30,000 cuneiform tablets and hundreds of other objects. The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures (ISAC) of the University of Chicago began digging at Nippur in 1948; this is the longest-running ISAC excavation in the Near East. Limited funds for the early seasons forced the field directors at the time, Donald McCown and Richard C. Haines, to carry out each season as if it were the last. Therefore, effort was concentrated on the religious quarter to which Nippur owes its historical importance. The layer-by-layer excavation of three temple areas and private houses resulted in the finding of thousands more tablets. Just as important was the establishment of two archaeological sequences that remained the standard for Mesopotamia until recent work at Nippur showed that they needed changes and additions.

11th to 19th Seasons

The 1972 season saw a new approach to Nippur. The new field director, McGuire Gibson, committed the expedition to a long-term program of excavation in the whole city. Emphasis shifted to the West Mound, a predominantly residential and administrative quarter of the city which had not been investigated since 1900. Shifting from the religious area was designed to give a more balanced view of the city. Nippur was sacred, but that was only one aspect of a thriving urban complex.

Several seasons were spent in excavating bakers' houses, a palace, and a sequence of temples on the West Mound. More recently, the expedition has concentrated on the low, flat area at the southern corner of the site, where excavations had never been made. Houses, large public buildings, and parts of the city walls dating to different periods were uncovered there. Among the results of these investigations has been the verification of information given in a unique plan of the city on a clay tablet from about 1250 BC. Subsequently, the team carried out investigations in a number of locations, including the city wall at the eastern side of the ziggurat and a small Islamic mound outside the city defenses. The 1970s and 1980s field work produced thousands of artifacts, including bronzes, jewelry, cylinder seals, and tablets. There was, of course, much pottery, and new approaches to the study of this valuable class of artifacts allowed the team not only to correct errors in the archaeological sequences but also to suggest functions for specific areas and even rooms of buildings.

In its work, the expedition treated Nippur as a laboratory where answers to a variety of questions about ancient life can be found and analyzed. It combined information from the artifacts and written sources with natural specimens. Samples of bones, seeds, pollen, and soil were studied as part of a program to reconstruct the ancient environment and its relationship to the city's population. In 1972, the Nippur Expedition was the first to include a soil specialist on its staff and to carry out flotation techniques for seed retrieval in the excavation of a Mesopotamian historical site. The expedition also pioneered in the use of computers for mapping, drafting, and data recording in Iraq. Advanced students were assigned areas to excavate and used the materials for doctoral dissertations. Sometimes their work involved the restudying of older dig records in light of new excavations and valuable insights resulted. In this way, the expedition not only brought more of Nippur to light, but also trained a new generation of Mesopotamian archaeologists.

Resumption of Work at Nippur

ISAC's decades-long archaeological and philological research at Nippur resumed in April of 2019 after almost 3 decades of hiatus. After McGuire Gibson retired in 2018, Abbas Alizadeh was appointed as the director of the Nippur Archaeological Expedition. Currently, Augusta McMahon serves as the director of the Nippur Archaeological Expedition. During the hiatus prior to 2019, all the previous excavation areas had been filled. The dig house had been ransacked, and all the tools and furniture had been looted. The dig house is now restored and furnished, and the necessary tools are purchased.

Much of Nippur had always been covered with sand dunes, but recently most of the dunes are gone, providing a great opportunity to prepare a new topographic map of the site and to create a GIS data bank. Because the entire government has been changed after the fall of Saddam Hussein, with new rules and regulations, the 2019 season of excavations was an exploratory one to assess the working conditions and feasibility for major exploration at the site. Accordingly, the work was limited to two areas on the Western mound where monumental Parthian architecture and a small Late Sasanian house were unearthed. In 2020, the expedition will expand to include several field archaeologists, geomorphologist, a paleozoologist, and a paleobotanist.

Articles

- 1993 Article: Nippur, Sacred City of Enlil, Supreme God of Sumer and Akkad

- 1992 Article: Patterns of Occupation at Nippur

- 1990 Article: Nippur, 1990: Gula, Goddess Of Healing, And An Akkadian Tomb

- 1978 Article: Nippur Regional Project: Umm al-Hafriyat

Annual Reports

- 2014-2015 Annual Report

- 2013-2014 Annual Report

- 2012-2013 Annual Report

- 2011-2012 Annual Report

- 2010-2011 Annual Report

- 2009-2010 Annual Report

- 2008-2009 Annual Report

- 2007-2008 Annual Report

- 2006-2007 Annual Report

- 2005-2006 Annual Report

- 2004-2005 Annual Report

- 2003-2004 Annual Report

- 2002-2003 Annual Report

- 2001-2002 Annual Report

- 2000-2001 Annual Report

- 1999-2000 Annual Report

- 1998-1999 Annual Report

- 1997-1998 Annual Report

- 1996-1997 Annual Report

- 1995-1996 Annual Report

- 1994-1995 Annual Report

- 1993-1994 Annual Report

- 1992-1993 Annual Report

- 1991-1992 Annual Report

- 1990-1991 Annual Report

- 1989-1990 Annual Report

- 1988-1989 Annual Report

- 1987-1988 Annual Report

- 1986-1987 Annual Report

- 1985-1986 Annual Report

- 1984-1985 Annual Report

- 1983-1984 Annual Report

- 1982-1983 Annual Report

- 1981-1982 Annual Report

- 1980-1981 Annual Report

- 1979-1980 Annual Report

- 1978-1979 Annual Report

- 1977-1978 Annual Report

- 1976-1977 Annual Report

- 1975-1976 Annual Report

- 1974-1975 Annual Report

- 1973-1974 Annual Report

- 1972-1973 Annual Report

- 1971-1972 Annual Report

- 1970-1971 Annual Report

- 1968-1969 Annual Report

- 1967-1968 Annual Report

- 1966-1967 Annual Report

- 1965-1966 Annual Report

- 1964-1965 Annual Report

- 1963-1964 Annual Report

- 1962-1963 Annual Report

- 1961-1962 Annual Report

- 1960-1961 Annual Report

- 1955-1956 Annual Report

- 1954-1955 Annual Report